I have more to say on the sonnets, but, as I understand it, my “they were all written within three years” theory is not the general opinion in professional academia, and amateur scholars should take at least some care not to embarrass themselves — which is to say, I have some reading to do. I suppose I also ought to decide what I think about “A Lover’s Complaint”. In the meantime, I thought I’d write a short bit about another of the annexes to the temple of Bardolatry: the man’s portraiture; and of that annex, which itself is a broad and gloomily-lit room, I propose to illuminate no more than a single dusty corner.

There exist only two confirmed likenesses of Shakespeare, neither of which can be said to be taken from life; all the rest is greater or lesser surmise. The first is the funerary monument in the Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon, near beside his grave; “thy Stratford moniment”, as Leonard Digges put it in his commendatory poem in the First Folio. Digges’ reference shows that it already existed in 1623, when the Folio was published. Likely enough it existed within a couple of years of Shakespeare’s death in 1616 - erected by his friends. Quite possibly it was sculpted from Shakespeare’s death-mask (which some have claimed still exists, and is somewhere in Germany - on that question I pass no judgement). Looking at the funerary monument, I would be surprised to learn that it was a good likeness of anyone — it does not seem to me well executed. Nevertheless, it is an image of the Bard deliberately erected by his contemporaries, and we must therefore take its testimony seriously, if not literally.

The second such image is the engraving made by Martin Droeshout as the frontispiece for the 1623 Folio, of which Ben Jonson tells us:

This Figure, that thou here seest put,

It was for gentle Shakespeare cut:

Wherein the Graver had a strife

with Nature, to out-do the life[…]

Well, strife indeed. Nevertheless, Jonson goes on to tell us “he hath hit/ His face”, and we must therefore accept, on the direct testimony of those who knew him in life, that this is what Shakespeare looked like — or it is at least close enough that his friends could recognise him.

That’s it for the direct testimony of Shakespeare’s contemporaries. Martin Droeshout was only fifteen years old when Shakespeare died. It’s therefore unlikely that Shakespeare sat for the above portrait. It was almost certainly commissioned for the First Folio, and copied from an existing portrait. Does this portrait still exist?

Yes, here it is.

Known as the “Chandos” portrait, this picture now belongs to the National Portrait Gallery. Experts (yes, they) have concluded that it most likely does depict Shakespeare. Okay, so what reason is there to think that Droeshout used it to make his engraving? Here’s one reason:

It’s clear from Droeshout’s oeuvre that he was not a particularly talented artist. If the engraving is intended to be a copy of the portrait, there are clear drafting errors: the misplacement of the ear and neck; the shifting forwards of the hair and the back of the head; and the concomitant forward bulge of the top of the head. I have a theory as to how these errors came about — for another time — but at any rate an astonishing coincidence of the features of the face must be admitted.

The Chandos portrait dates from the first decade of the 17th century. Shakespeare would be somewhere between 36 and 46 years old — believable, I think, given the image. It should also be said that the image is discoloured and has not been restored; forensics suggest also that it has been retouched at a later date: both the hair and the beard have been extended. Therefore the resulting likeness is not precisely as the man looked. However, it is likely that this portrait is of Shakespeare, that it was taken from life, and it seems to have been made by a skilled artist.

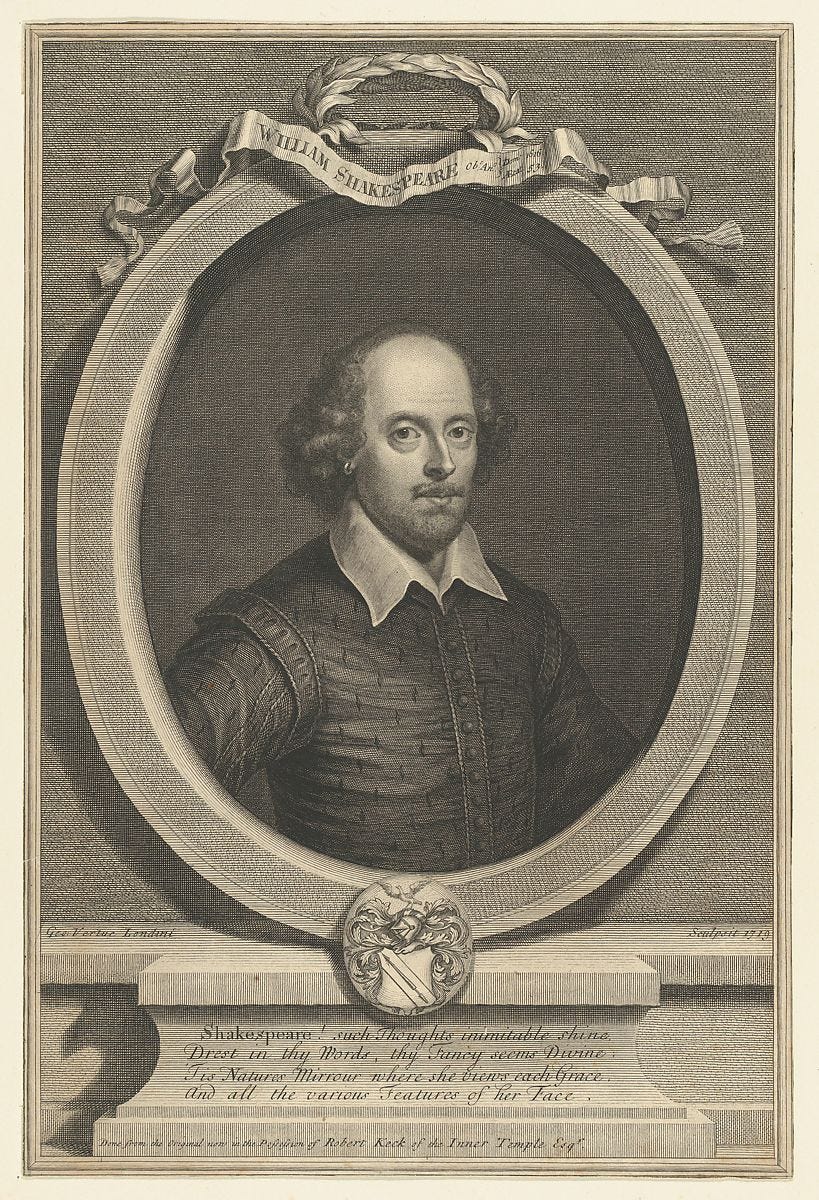

Above is an engraving made by George Vertue for a set of plates issued circa 1730 entitled “Twelve Heads of Poets”. An artist who out-talented Droeshout in every way, Vertue has also based his engraving on the Chandos portrait. You may be able to see the text at the bottom which attests that the original from which the engraving was made was owned by Robert Keck Esq. Robert Keck was a collector of Shakespeare memorabilia, and we know that what is now called the Chandos portrait was once in his possession. After Keck died it was inherited by one John Nichol, who married into the Keck family. Nichol’s daughter married James Brydges, the 3rd Duke of Chandos.

Vertue kept notebooks, and in them we learn that Robert Keck had purchased the painting from an actor, Mr. Betterton (for 40 guineas — a lot of money), who himself had it from one W. Davenant, who had it from Shakespeare himself. William Davenant was the poet laureate who succeeded Ben Jonson. He was the son of John Davenant, once mayor of Oxford and proprietor of the Crown Inn, where, it was said in the decades after Shakespeare death, the Bard had frequently stopped while travelling back and forth between London and Stratford. It was rumoured that Davenant was Shakespeare’s godson; it was rumoured also (perhaps at Davenant’s own instigation) that he was his illegitimate child. At any rate, Davenant, at the tender age of twelve, wrote a poem entitled “In Remembrance of Master Shakespeare” (1618), so a personal connection seems likely. If Vertue’s account of the painting’s provenance is not the truth of it, it is a curiously compelling forgery.

Okay, enough. I’m happy to conclude that the Chandos is indeed a portrait of William Shakespeare taken from life and if you’re not, we can part ways here amiably. I did not come here to talk about the most-likely life portrait of Shakespeare, which any respectable academic could have told you about, but the second-most-likely — whose more speculative nature makes it the proper purview of just-some-guy-on-the-internet.

In 1725 a new edition of Shakespeare’s works was published, edited by Alexander Pope. Shakespeare’s meter (often loose but always tasteful) was “corrected”, and lines which he thought were not written by Shakespeare, but by his actors, were removed. He also spent much of the preface explaining what he saw as Shakespeare’s faults. Well, Pope’s gonna Pope. Here’s the frontispiece of the 1725 edition:

The eagle-eyed reader may have noticed that this image, too, was made by George Vertue — and that it was made after the image for Heads of Poets (1721 and 1719 respectively). Which is to say, Vertue had already made his copy the Chandos portrait (at that time, the Keck portrait), when for some reason he elected to make a second picture of Shakespeare. This time the original was owned by one “Edwardum Dominum Harley” — Edward Lord Harley, the 2nd Earl of Oxford and Earl Mortimer. He was the son of Robert Harley, who preceded Robert Walpole as a sort of proto-Prime Minister under Queen Anne. Edward Harley was a collector of antiquities and patron of the arts. It seems he owned a portrait of which Vertue made a copy — and called that copy “Shakespeare”.

This frontispiece has caused some consternation on the entire reasonable grounds that it doesn’t look very much like Shakespeare. Some have concluded that Vertue has copied the portrait of some, yes, Jacobean gentleman, but was confused about the person’s identity; and indeed it was replaced in Pope’s 2nd edition of the plays by yet another copy of the Chandos. But Vertue had already made his copy of the Chandos portrait before he copied Harley’s portrait, and when it came to printing Pope’s edition of the plays, they chose the latter. It’s clear that Vertue and Harley at least must have believed that this was a true portrait of Shakespeare — so what became of it?

Edward Harley inherited Welbeck Abbey in Nottinghamshire through his wife, along with a collection of miniature portraits which had come to her from her ancestors: the Cavendishes and the Holleses; this may be how he first came into possession of the “Shakespeare” portrait, though he was a prolific collector in his own right (Dr. Johnson would later say that his library “excelled any library that had ever been offered for sale”). After Harley died, his widow employed Vertue to make a catalogue of his collections. Sadly, this catalogue has been lost. Harley’s only surviving child, Margaret, inherited the lot. She married William Bentick, 2nd Duke of Portland — and so Welbeck and its collections were passed on through his line. Under the 6th Duke of Portland, in 1916, a new catalogue of the miniature portraits was made, and thanks to the modern luxury of Internet Archive’s book digitisation program, we can see it.

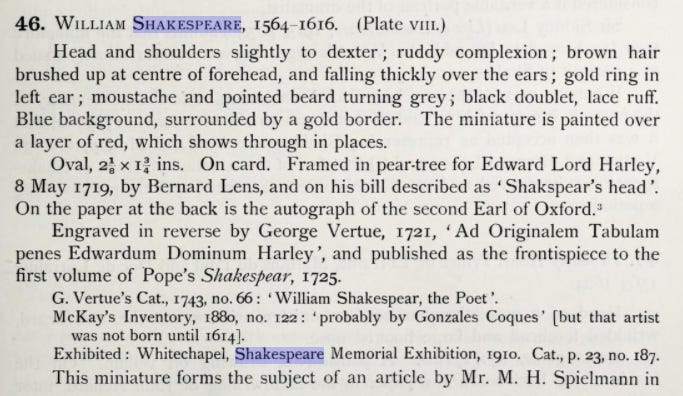

I’ve no suspense to keep you in, so I’ll just show it, shall I?:

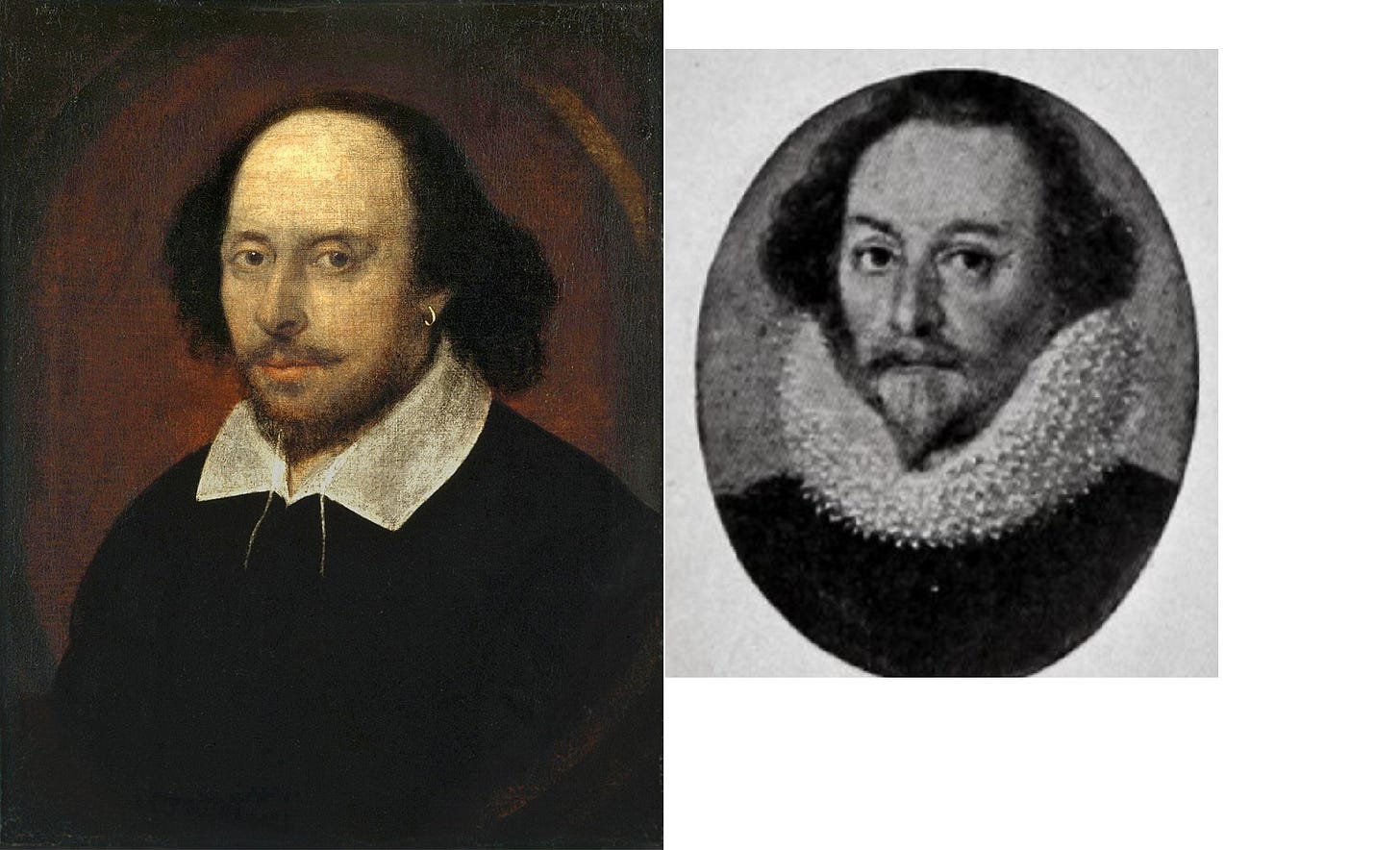

It’s quite clear that this is the portrait that was used as the basis for Vertue’s engraving. Let’s see them side-by-side.

The chief defect of Vertue’s rendering, I think, is in the nose. He has softened the lighting, and this has taken the edges off the gentleman’s snout, making it look rather fleshier than in the original. Of course, it’s hard to tell; we’re working from a digitisation of a black-and-white photograph taken in 1916. Here is the catalogue’s description of miniature 46:

(Those who have encountered the spurious arguments of people who indulge in the “Authorship Question” will be amused to see that even as late as 1719, “Shakspear” was an acceptable spelling of the Bard’s name.)

Whatever one thinks of the portrait itself, it is clear that Harley and Vertue agreed around 1720 that it represented Shakespeare. Both Vertue and Harley were Shakespeare obsessives — in a way, the first generation of Bardolaters — and antiquarians both. In fact, to draw together the various strands of this essay:

Above is a quick sketch made by Vertue in the Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon. Paying obeisance to the monument of Shakespeare is the foppish, periwigged figure of Edward Lord Harley, Vertue’s patron.

Unfortunately, we don’t know how Harley acquired the number 46 miniature — if we are therefore to conclude that it is Shakespeare, we will have to take Harley and Vertue’s word for it. We might reflect, though, that while the frontispiece of Pope’s first edition resembles not at all the Droeshout portrait from a century earlier, the portraits on which they were based do bear a certain resemblance.

The gentleman on the right is older and more haggard, but in the shape of the nose and the eyes, the width of the mouth (less pleasingly set in the Welbeck image), in the narrowness of the brows, the softly sloping jaw towards a rounded chin, the images are consonant. Note, also, that the description of the Welbeck original assures of a “gold ring” in left ear; this is not visible in the black-and-white reproduction, but is replicated by Vertue. We might also note that the “Van Dyke” facial hair matches that depicted on the funerary monument. If these two pictures are of the same man, we can’t say that the years separating them have treated him kindly; rather they suggest growing wealth, and failing health. But that’s late middle age, I suppose.

My confidence in the Chandos portrait is not replicated by the Welbeck, but as I’ve said I think it is the second-most-likely portrait-from-life of the Bard. If you push me, I think I’d say I consider it more likely than not. A century is a long enough time to compose a fraud, but if it is a fraud — and a convincing enough fraud to fool both Harley and Vertue — it is not built along the more obvious lines. It is not, like the so-called “flower portrait”, a copy of the Droeshout engraving reproduced in full (imaginary) colour. And if it is a copy of the Chandos, then it is ingeniously done: the ageing-up, the recollaring, the slight turn of the head towards straight-on. One avenue of doubt, however, yawns open: Vertue, at least, and probably Harley too, had seen the Chandos portrait. Is it possible they came across a miniature portrait which just happened to resemble the Chandos, and in a fit of enthusiasm declared it “Shakespeare”? It could be so. I’m not sure it’s the most likely explanation.

In any case, it seems odd to me that I haven’t been able to show here the Welbeck portrait in full colour and detail, rather than relying on a smudgy black-and-white reproduction from 1916. The reason for this is: I simply cannot find a full-colour image of it on the internet. I don’t even, in fact, know where the portrait is now, or whether Welbeck Abbey’s collection has been kept intact through the last century. It’s surprising to me that this portrait has received so little attention. Perhaps there is some reason I’m unaware of which has caused the experts in this field to conclude that it’s not Shakespeare after all.

If it is Shakespeare then, given the age of the man depicted, it might well have been the very last image made of him. I’d like to see the damn thing.

There is an excellent essay on the Welbeck 'Shakespeare' by M. H. Spielmann in the January 1913 edition of the Connoisseur which is pretty much dismissive of the identification.